Double Dutch?

Observing people from different linguistic backgrounds learning a language is almost as interesting as mastering a new language itself.

Observing people from different linguistic backgrounds learning a language is almost as interesting as mastering a new language itself.The majority of my Spanish class is German. In addition to their mother tongue, almost all of them speak fluent English and French; and judging from their keen participation in class, their Spanish is coming along rapidly.

If we compare a European adult who has been exposed to various European languages from infancy with someone, say from Australia, who has been brought up in, save a few years of classroom French, an essentially mono-lingual environment, their varying abilities to master a new language in adulthood provide interesting insights into the development of linguistic intelligence in the human brain.

In the first years of an infant's life, the brain is busy building its wiring system. Activity in the brain creates tiny electrical connections called synapses. The amount of stimulation a young child receives directly affects how many synapses are formed. Repetitive stimulation strengthens these connections and makes them permanent, whereas young connections that don't get used eventually die out.

In other words, the brain is like a group of muscles; they grow bigger and stronger if they get used and trained regularly. On the other hand, if parts of these muscles are left untrained until much later in life, it becomes harder for them to function as well as the developed muscles in others with an early start.

Hence, timing is an important factor in the acquisition of intelligence, especially linguistic intelligence. The first years are the pivotal time for a developing young brain. This intense period of brain growth and network building happens only once in a lifetime. This is the time, a window of opportunity, to stimulate the young minds and encourage them to use all their facilities. Acquisition of knowledge prepares the brain for more knowledge; hence, mastering a second language helps learning a third and more. Learning becomes easier the more one learns.

An adult may still be able to learn and master a second or more languages which share similarities with their mother tongue such as an English speaker mastering French and may be another European language. All three languages are based on alphabets and share some Latin roots or grammar structure. However, it is difficult for someone learning these languages as an adult to reach the same proficiency of say, a Swiss or a German who has grown up in a multi-lingual environment.

Then, things start to look decidedly grimmer if an adult departs from his/her linguistic base to learn a language of a distinctly different culture.

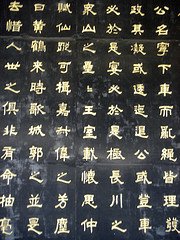

Guillermo has started his Mandarin course and despite being a focused learner armed with cognitive memory techniques, he struggled, in the beginning, with the oral aspects of a completely tonal language. Further down the track, he will struggle even more if he decides to learn how to write.

The written language is based on hundreds of thousands characters; each character is made up of a number of components and stands for a concept. To have the literacy of an educated adult, he would have to understand and write at least tens of thousands of characters.

An adult's brain is already pretty full to make room for these characters; in other words, his muscles have been developed and won't grown too much bigger or be strong enough to handle the entire additional load.

I, of no exceptional intelligence, started learning both Chinese and English at kindergarten. While English was decidedly a second language in my infant years, nonetheless, the two unrelated language systems were being absorbed by the brain from infancy. When my environment changed into a fully English one at age 12, I already had enough Chinese under my belt to continue my education through self-learning. Today, I am equally comfortable in both languages. Further, I've gone on to learn Italian which then helped me to understand some French and now Spanish.

Guillermo and I have always been intrigued by parents who consciously decide to keep their children's environment mono-lingual, thinking that is of any benefit at all. In doing so, they have unwittingly limited the growth of their children's linguistic muscles.

For this reason, I am evangelical about the more vigorous bilingüe (bilingual) schools in Argentina. I recall chatting with an eight year old girl who goes to Oakhill (a bilingüe primary school in the Northern suburbs), the daughter of one of Guillermo's cousins. Both parents are Argentine and their girl, Candi, is completely fluent in English and Spanish.

Even kids from the best private schools in Australia where French is commonly taught as a second language, one would be hard pressed to find any young French speaker who has mastered their second language with the same depth and speak it with equal ease. Well done, Argentina!

<< Home